By Matt A. Mayer

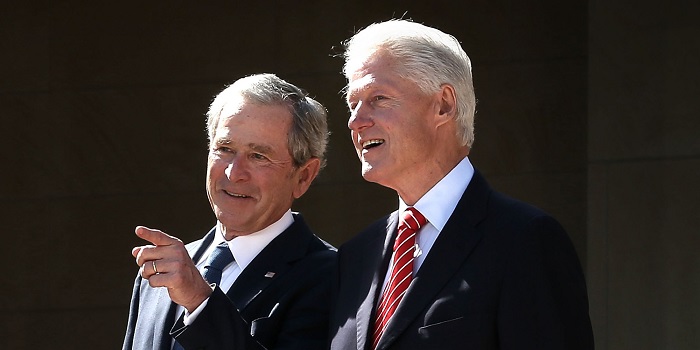

As Winnie the Pooh is fond of saying to his friends in the 100 Acre Wood, I am a bear of very little brain. So, unlike all of those Ivy League graduates who (over)populate elite institutions like the Federal Reserve, the U.S. Treasury, the White House, and the Congress, I try to keep things simple. The mess we are in today is nothing more than the readjustment necessary to eliminate the unjustified and/or ponzi-like growth that occurred in the stock and housing markets during Bill Clinton’s and George W. Bush’s presidencies.

From the Tulip mania in 1637 Holland to the South Sea Company bubble in 1720 and the Railway mania in the 1840s in Britain to the Florida land boom in the 1920s to today, it appears that we are incapable of remembering the old adage that if it sounds too good to be true, it is. Over the last thirteen years, despite centuries of history’s lessons, we ignored those lessons and the warning signs along the way in search of a quick buck. Shame on us.

Just as Amity Shlaes and other experts have shed new light on the Great Depression and forced a much-needed reevaluation of the wisdom and utility of the New Deal policies promoted by Franklin Roosevelt, historians and economists need to begin reevaluating America’s “lost decade” that began in 1995 and ended in 2007. Just as FDR erroneously took credit for getting America out of the Great Depression, Clinton erroneously takes credit for the economic boom that occurred during his presidency, but went bust shortly thereafter. As we know, Clinton’s economic boom was fueled by the dotcom bubble and shady accounting practices that led to the Enron and countless other company meltdowns, as well as risky housing policies that disconnected the risk of the borrower from both the size of the mortgage and the equity required to put down on it.

As the stock boom went bust in 2000 and 2001, people rushed to “safer” assets like real estate. The housing market went gangbusters as the federal government added more fuel to the Clinton campfire by pushing Freddie Mae and Frannie Mac to support even riskier loans to people even more unworthy of credit and with no skin in the game. The Clinton campfire turned into an uncontrolled Bush forest fire ripe with speculators, fraud, and the ponzi-like notion that housing prices would always increase, thereby allowing the pyramid to grow as those first in got paid by those behind them. The housing pyramid collapsed when those at the bottom couldn’t find any more suckers to enter the game and the banks came calling.

Two measures vividly demonstrate the folly of the last thirteen years.

First, from March 1954 to December 1994, the Standard & Poor 500 Index had a 6.61% annualized growth rate. On December 9, 1994, the S&P 500 traded at 446.96. From that day until May 24, 2000, it grew by 242%, or an annualized growth rate of 26.15%, to a then record 1,527.46. Even the dotcom and corporate fraud bust failed to totally squeeze the inflated gains out of the market. On January 19, 2001, the day before Bush started his presidency, the S&P 500 traded at 1,342,54, which was still a 200% net gain from December 1994 or a 19.71% annualized growth rate. At its post-September 11, 2001, bottom on October 4, 2002, the S&P 500 traded at 800.58, which was 79% gain over eight years or a nearly 8% annualized growth rate.

By early 2003, the S&P 500 started another bull market run, this time fueled by Main Street consumer spending using credit cards and the funds pulled from inflated home equity, by the Federal Reserve’s loose monetary policy, and by Wall Street’s too clever by half derivative packages. It reached a new record close of 1561.80 on October 12, 2007, which represented a net growth of 95% in five years or a 15% annualized growth rate. Then, it all came crashing down – not just to the Bush era beginning, but the crash reached back to the Clinton era beginning, too.

The reality is that the current trading price at around 900 is where the S&P 500 would have been had it grown at 5% per year, which is close to the pre-December 1994 annualized growth rate. Since October 9, 2008, the S&P 500 has traded around the 900 mark, indicating that the stock market has stabilized. Given the economic recession, it is possible that the market will drop even more as consumers further tighten their wallets, the housing market declines, and government weakens the dollar with unprecedented rate cuts and by continued profligate spending.

The second measure is the Case-Shiller Home Price Index. The historical average yearly growth rate for housing for the ten-year period before 1997 was roughly .19%. In January 1997, the C-S Index stood at 78.08. From that month to June 2006, it rose to the dizzying height of 226.29, which equated to a 190% net increase, or 20% per year average gain. Such an increase was utterly unrealistic and unsustainable.

In the twenty-seven months from June 2006 to September 2008, the C-S Index dropped to 173.25, which is a 23% decrease. As with the S&P 500, had housing prices increased each year more closely to the historical averages of the 1987 to 1997 period (.19%) or even the full 1987 to 2008 period (.38%), the C-S Index today would stand at between 102.13 and 131.94. This means that housing prices should continue to drop for the next twelve to eighteen months until the remaining inflated growth is squeezed out of the market.

As the S&P 500 and the C-S Index settle into their historical growth patterns, we must face the consequences of the “lost decade.” For Americans who lived beyond their means or speculated during the bubble, that equates to bankruptcies and foreclosures. For those of us who played by the rules, that means significant losses in our retirement and our kids’ education accounts, as well as “paper” losses in our home equity. While painful, those of us still employed and young enough have time to rebuild. We are the “lucky” ones.

The Clinton/Bush recession also means the loss of jobs, delayed retirements, and retirements suspended for many Americans. For them, we must hope that the recession doesn’t get worse or last too long so that they can get back on their feet.

While unlikely, let’s hope we have finally learned the lessons of the last four hundred years. After all, it doesn’t take an Ivy League degree to know that when you stick your hand in a beehive to get honey, there is a very good chance that you and the innocent around you will get stung.

This article originally appeared on Townhall.com.